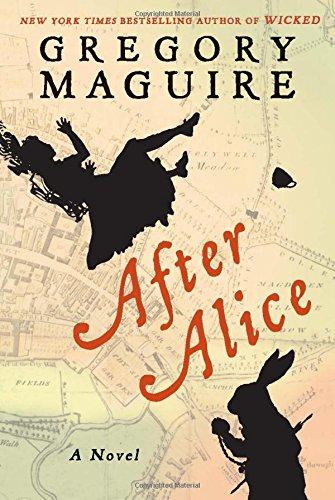

Maguire's AFTER ALICE Heavy on Weird, Light on Wonder

FTC Statement: Reviewers are frequently provided by the publisher/production company with a copy of the material being reviewed.The opinions published are solely those of the respective reviewers and may not reflect the opinions of CriticalBlast.com or its management.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. (This is a legal requirement, as apparently some sites advertise for Amazon for free. Yes, that's sarcasm.)

I have a confession to make. I've never read a Gregory Maguire book before. I know the name, I know the fame, and I've even seen the musical, WICKED, based on his novel of the same name. But I just hadn't sought out any of his works to try them in their written form.

And then I saw AFTER ALICE. When it comes to Alice in Wonderland books, I'm much like Mel Gibson's character in CONSPIRACY THEORY who, whenever he saw a copy of CATCHER IN THE WRY, he felt compelled to buy it. So I picked it up and looked forward to another trip down the classic rabbit hole.

Maguire's tack is to write a sidequel -- like Orson Scott Card's ENDER'S SHADOW -- following a friend of Alice who also fell down the rabbit hole but whom Alice never saw. Ada Boyce is a young girl bound up in a metal body brace to straighten her spine. Her father is a distracted vicar, her mother is alluded to be a bit of a drinker, while the family deals with a dispeptic infant boy. Instructed to take a jar of marmalade to the Clowd family, Ada gets out ahead of her governess, Miss Armstrong, and enjoys her newfound freedom. She comes across Alice's elder sister, Lydia, reading her dissertation on A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM, and soon after follows the White Rabbit down the same hole Alice went down, intent on finding and rescuing her erstwhile friend, and losing her armor along the way a la a teenaged Forrest Gump.

However, Ada isn't the only story being told here, as Maguire also covers the rest of Alice's and Ada's family to relate the goings-on during the girls' disappearance. It is worth nothing here that Maguire has given Alice's family the name Clowd, not Liddell, and the patriarch of the family is not the Dean of the college but a man of conflicted faith in the wake of his wife's death a few years past. He's also playing host to Charles Darwin during the naturalist's later years. While this doesn't necessarily conflict with AAIW (indeed, Lewis Carroll himself tried to make sure there was a distinction between Alice Pleasance Liddell and Alice the Dreamchild), it is a bit jarring for those who are close to the source material.

Lydia and Miss Armstrong become saddled with each other in the search for the two girls -- and later a young boy, an escaped slave named Siam, who is the charge of the American Mr. Winter, who is Darwin's aide-de-camp. (Siam escapes a minor punishment by escaping through a looking glass.) Lydia is haughty, and fancies Mr. Winter. Miss Armstrong is emotionally unstable, with feelings for her married employer, Mr. Winter, and even having an eye cast toward the widower Clowd.

Following Ada's adventures, we encounter once again Hatter and Hare at the Mad Tea Party, as well as the Cheshire Cat. The author also has her encounter Humpty Dumpty and the White Queen, although those characters didn't appear in AAIW but rather in THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS. The encounters don't engage in near the level of playful nonsense as Carroll's work. Indeed, the more Wonderland-like place is Maguire's real-world level, where we have talk of Dodo's and endure a live reenactment of Pig and Pepper (of sorts) in the Boyce household. Charles Dodgson himself does make an anonymous cameo appearance as Lydia and Miss Armstrong search the roads of Oxford for the missing girls, which was a nice tip of the hat to the source of the material.

On the whole, the language of AFTER ALICE will wear down a new thesaurus to the nub, which lessens the approachability of the novel to any readers without a masters degree in English literature. Moreover, when we're not bouncing around between POVs, we are often taken out of the story by the narrator who inserts himself into the story, delivering homilies to the reader, directing attention to this thing or that, pointing out things that would happen in the future, or establishing a colorful observation of the mise en scene.

Dry, sesquipedalian, and devoid of the delightful humor that made AAIW an enduring classic, AFTER ALICE joins a lengthy list of novels inspired by something that has been often imitated and never duplicated.