Brennan Lafaro's Bloody Horror-Western Novel 'Noose' Misses The Mark

FTC Statement: Reviewers are frequently provided by the publisher/production company with a copy of the material being reviewed.The opinions published are solely those of the respective reviewers and may not reflect the opinions of CriticalBlast.com or its management.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. (This is a legal requirement, as apparently some sites advertise for Amazon for free. Yes, that's sarcasm.)

Ah, the Wild West. The mere mention of the term arouses near-mythic associations profoundly embedded in the American national psyche. That period of Manifest Destiny, of expansive vistas and painted horizons. Cowboys and Indians, desperadoes, cattle rustlers, long nights on the open range, showdowns at high noon. Jesse James and Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and the shootout at the O.K. Corral. Even while it was happening, the era of westward expansion was being romanticized in dime novels and newspaper articles fed to a public fascinated with the lawless frontier, and the advent of Hollywood only cemented that legendary legacy in the cultural consciousness.

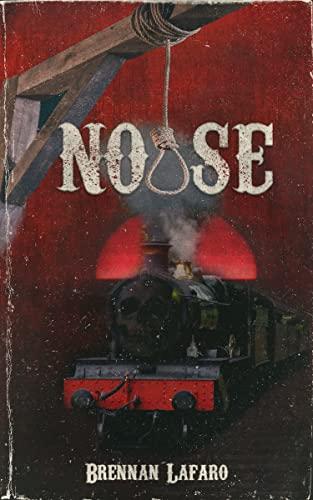

In literature, too, the western holds no minor prominence. Grown up from those garish 19th century rags into one of the pillars of publishing, it’s flourished in modern times due to an easy hybridization with other genres. Countless romance novels employ western motifs, and a surge in ‘horror-westerns’ inspired by the weird writings of Joe R. Lansdale and movies like Ravenous, The Burrowers and Bone Tomahawk has taken root in recent years. It’s in this latter vein that leading indie horror publisher DarkLit Press releases Massachusetts-based author Brennan Lafaro’s latest splatter epic, Noose.

Our adventure begins in 1872, when the well-to-do Daggett clan—William, his wife, Mae, and their eight-year-old son Rory—have the misfortune to be aboard a train going back to their dry gulch Arizona town of Buzzard’s Edge the day notorious outlaw George ‘Noose’ Holcomb decides to rob it. Renown for his savagery, Holcomb gleefully murders everyone aboard before absconding with the passenger’s valuables. Everyone except Rory, that is. Intentionally left alive by Noose, the boy is taken in by the kind yet poor Taff family and comes of age under the dreadful shadow of that deadly day. Always fearful Noose will return to finish what was started, Rory nonetheless spends his time searching for Holcomb in the hopes he can claim vengeance. When, after fifteen years, Rory tracks down one member of Noose’s elusive gang, he learns he was correct to think Holcomb was keeping tabs on him, and a violent cat-and-mouse game ensues that sees Rory work his way through Noose’s collaborators one-by-one until he comes face-to-face with the monster who made him.

There’s rarely a dull moment in Noose. Rory’s hunt for Holcomb is briskly-paced, two-fisted pulp sport, filled with roaring action, flying bullets and bountiful bloodshed. Devotees of the stranger side of speculative fiction will appreciate the unorthodox figures Lafaro populates his world with, particularly Holcomb’s accomplices: there’s the deranged chemist, Simon Crane; Edwards, the riddle-me-this knife thrower; inhuman brute Dorrance, and Merella, the witch whose spells provide mystical protection to both Holcomb and the entire gang.

That said, Noose suffers its share of valleys. Those less desirable qualities include a malnourished plot, anorexic characterization and a setting oddly starved of western-style detail. The late 1800's were indeed a raw, unlawful epoch in American history, but the book fails to fully grasp the time’s feel. The saying may be true that the west is a state of mind as much as a setting, but the latter inspires the former, and it’s to the novel’s detriment that the sense of place is ill-defined. Buzzard’s Edge, its environs, structures and citizens, are scarcely more than a rough sketch: Tombstone or Deadwood or Dodge City this surely ain’t. Even Lafaro’s choice of terminology seems curiously out-of-tune with the genre (Sure, there’s a tavern in town, but the unused-anywhere-in-the-novel word saloon conjures an instantaneous association with the old west that tavern does not), and while he boasts in the afterword of taking ‘...a lot of research breaks in the writing and a lot more during the editing’, there exist unforgivable blunders that even casual readers will likely notice. For a book dedicated to gunslinging, the author’s repeated confusion of revolvers and pistols consistently irritates (one line laughably reads, ‘My eyes surveyed the empty room while I dug out two more rounds and refreshed the pistol’s cylinder.’). Each weapon is a distinct type of handgun (revolvers have cylinders, pistols do not), and their misuse pulls a reader, however briefly, from the story.

Told from Rory’s perspective in a breezy, conversational, first person tone, the narrative frequently rambles and lacks the gritty gravitas often coupled with the genre. Aside from Rory himself and his sometime comrade-in-arms, Sheriff John Harden, the characters are uniformly one-dimensional. For all the bother made about Holcomb and his gang, they appear only as ciphers, their full heinous potential unrealized. Holcomb’s motivation for showing such vicious, long-standing interest in Rory is never satisfactorily explained, and while the ultimate confrontation grants some small catharsis, it’s disappointing that more space wasn’t dedicated to the encounter. After suffering alongside Rory for an entire novel, his vendetta against Holcomb, however poignant the resolution may be, seems too easily concluded.

Overall, Noose as a book has less in common with the enviable epics of Larry McMurtry or Louis L’amour or Zane Grey than it does with DC Comics icon Batman. Consider: a young boy witnesses the grisly murder of his affluent parents, devotes himself to hunting down their killer while encountering a rouge’s gallery of unlikely, cartoonish criminals along the way (villain Edwards, with his annoying enigmas, is reminiscent of The Riddler, and Simon Crane’s chemical concoctions are similar to The Cape Crusader’s adversary Johnathan Crane, a.k.a. The Scarecrow). Like Bruce Wayne, Rory is a child of privilege and uses his parents’ stately manor for his headquarters. He even acquires a kid sidekick, Alice, who, like Dick Grayson of Robin fame, lost her own family to violence and now assists Rory in his quest. The comic book flavoring doesn’t stop there, either: Noose’s closest creative kin isn’t Lonesome Dove, Unforgiven or True Grit, but DC’s long-standing Wild West weirdo Jonah Hex (a character the aforementioned Lansdale penned in the mid-1990’s). Like Hex, Noose revels in the bizarre, but where Jonah’s tales are buttressed by a strong sense of history and steeped in rich characterizations, Noose falters.

For all its frustrations, Noose still isn’t a lost cause. A supplementary novella at book’s end, Come and Take My Hand, detailing how a youthful George Holcomb started down his twisted path to villainy, provides much a stronger dose of western atmosphere along with a genuinely unnerving narrative. For those interested, another of Lafaro’s yarns set in Buzzard’s Edge, a pleasing detective story starring Sheriff Harden, ‘Trade Secrets’, appears in the Brigids Gate Press anthology Blood in the Soil, Terror on the Wind, edited by Kenneth W. Cain.

After all is said and done, Lafaro’s novel has its (bloody) heart in the proper place, and fans seeking a quick jolt of gore will find themselves giggling giddily over every gruesome passage. For those expecting something deeper to accompany the mayhem, however, Noose just misses the mark. Taken on its own, I give it a 2 (out of 5) on my Fang Scale. If Come and Take My Hand is added to the mix, raise the score a half-point. Happy trails, pilgrim.